Sometime in the late Eighties, during my school days in Secunderabad, I watched a movie on television that left a strange impression on my mind. I must have been thirteen or fourteen, a typical Indian teenager fond of cricket, comics and movies. (Girls were only a curiosity, but that would change soon.) Every Sunday I would check the Deccan Chronicle for the scheduled evening movie on Doordarshan, and if it looked interesting I would be home in time for the 5:45 pm “Hindi Feature Film”. There was a Black & White TV at home, an Uptron portable fourteen inch with a V-shaped antenna that stuck out like a pair of bunny ears, and Doordarshan, you’ll remember, was the only channel we received those days.

On this Sunday the movie, Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro, was not one I’d heard of before, and there were no big stars listed either. But the name intrigued me for some reason, so that evening I skipped a game of cricket and settled myself on the sofa at a quarter to six. The next two and half hours had me in splits. I don’t remember laughing so much to a movie before, and since then only Johnny Stecchino, starring the incomparable Roberto Benigni, comes anywhere close. But there was one problem with Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro: I did not understand the ending, which left me sour and confused all evening, and I decided I didn’t like the movie. Next day, at school, I asked my classmates, but no one had cracked the puzzle. Why did the Vinod and Sudhir, dressed as prisoners, make that throat-slitting gesture? Were they to be hanged? Or were they already ghosts, spirits of two innocent men who were hanged, wandering in Bombay like zombies? Why, after all that fun, did the ending need to be so tragic? It simply wasn’t fair!

But life isn’t fair, and the symbolic ending tried to underscore this point. Throughout the movie, beneath the humour there was a dark undertow of negativity and pessimism, a sharp commentary on the corrupt society, but this was all beyond my grasp – I had missed the subtext entirely, and the surface humour had kept me swimming all along. So when the subtext rose to the surface in that last scene (perhaps the only scene that was pure symbolism), there was nothing else to hold on to, and I sensed myself drowning, grappling with a conclusion I could make no sense of. Traumatic.

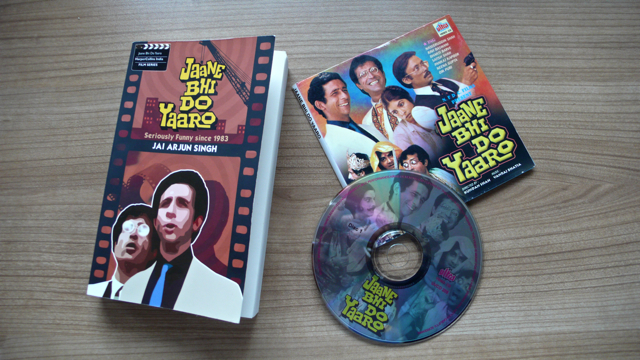

That scene, says Jai Arjun Singh in his book Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro: seriously funny since 1983, is “symbolism at its finest: it is a direct visual shorthand for the idea that the common man is in chains, his neck perpetually in a noose … [it is] like a coda that is cut off from the rest of the film.”

No wonder I had all that difficulty with the ending.

* * *

In a recent talk Jai Arjun Singh, speaking on why film criticism matters, observes that “a really good review will be a solid piece of writing on its own terms, something you can read and enjoy for what it is, for the craft that has gone into it, for the window it opens into a new way of watching a film and talking about it.” His book is all this, and more.

The book narrates the film’s journey from conception to release and to its eventual cult status. Beginning with Kundan Shah, the director, a “mild-mannered man in whose head the film first took shape,” it hovers like a camera over the film’s cast and crew, following them through moments of struggle, hope, despair, and laughter (much like the movie does with Vinod and Sudhir), and their reflections on the movie twenty seven years after it was released. This method lends it the texture of a novel, with a lean plot, well-sketched characters (whom we soon begin to empathize with), drama and conflict, humour, and an open-ended finish.

Early in the book, discussing the portrayal of social and political satire in films, Singh ruminates on a writer’s ability to “step outside of yourself … and see the lighter side of the situation”. He continues:

Half of you is participating in the world, seething about its injustices; the other half is standing by and coolly observing, taking notes to weave something funny out of it afterwards. It’s a variation of what Graham Greene called the sliver of ice in the novelist’s soul. Kundan had this ability.

Such insights, into an individual or into the art of film-making, give the book a delightfully instructional character. The theory, thankfully, never trumps the story, and the narrative advances steadily, spiced with humour and with behind-the-scenes masala, keeping you engaged.

The book evokes a different era of Hindi movies – of fledgling film crews struggling to manage under a tight budget, and the camaraderie and do-or-die attitude that drives such units; of the early days of film personalities that are household names now; of the irreverence with which you could treat some subjects in those days – and this gives it a timeless quality: nostalgia, unlike old film that gets mouldy with time, never really ages.

The author’s love for his subjects – film, film-making, and this particular movie – is evident throughout, but this does not stop him from asking, toward the end, some incisive questions about the film and its creator.

* * *

I watched the movie again last Sunday, before picking up this book, and a third time on Wednesday, after I finished the book.

The second viewing was like rediscovering a toy or a book lost long ago; familiar in its outlines, it still offered the thrills of experiencing scenes I had forgotten all about: Vinod and Sudhir with editor Shoba as a “model”; the press-conference with Tarneja; the hawaldaar at the flyover. And I could see why the ending – disjointed, abstract – had left me unmoored.

The third occasion was different again. The book had illuminated many scenes, which I could now experience and understand in a new way: the trials of shooting the Alibaug scene; the absurdity of acquiring a dead rat; the lip-sync inconsistency caused by a missing scene. I also noticed, and appreciated, the musical score, an element I had missed on the previous viewings.

There’s nothing new in discovering “the many layers of a work of art”. But these experiences of mine, spanning book and movie, brought this cliché to life, and, by revealing some techniques behind the art they turned me, for a brief period, into a keen student of film. The movie’s ending, however, continued to bother me. Was such a twist necessary? Was there a lighter alternative that packed the same punch? I was still turning this in my mind, unable to find a satisfactory answer, when I spotted the book cover lying in front:

Jaane bhi do yaar, it said, as if speaking to me. Just let it be, my friend.

This is the second blog I have read this morning on the subject of appreciating art. The other was Barrett Bonden’s “Works Well” (http://bbworkswell.blogspot.com/). I enjoyed both posts, yours and his. I could enjoy a string quartet because the language of music is universal, but sad to say, I couldn’t understand or appreciate the Indian movie.

The humour in this movie is hard to catch unless one is familiar with many elements of the Indian context. Not as universal as the language of music, I agree.

A few years ago I watched this Indian film at the HK Int’l Film Festival (which features a broad and diverse scope of films, of very uneven quality). The film is about an innocent voyeur who’s in love with the neighbor he spies on, ends up on the run with a friend, in a time of severe terrorist attacks around the city they live in. The protagonist and his friend are doomed, this you know from the start, but many parts of the movie are hilarious in spitefully absurd and fantastical manners…e.g. The city’s bus becomes, metaphorically speaking, a cradle past midnight that cheers up the poverty-striken, rocking around town (I’m sure it’s not exactly that in the movie – but it’s how I remember it). And the lady in the birth control ad becomes a real person, travels all the way to visit the protagonist. Up until a certain point the film has the markings of soap opera, then it’s a dark fable all over. The film is a little uneven, overall, but it sure left an impression on me.

http://calcuttatube.com/ami-yasin-aar-amar-madhubala-the-voyeurs-2008/1240/

Since then I’ve always wondered about Indian cinema (I generally only watch indie films) – after all, there must be many solid, indie film makers in Asian cinema who illuminate that lighter side of things in the utter absurdity of life, and the societies we live in.

I haven’t watched that one – thank you for the link, Nicolette. Yes, there’s a lot of interesting work being done these days in “indie” Indian cinema. You must check out Jai Arjun Singh’s blog if you are keen on this subject.

And I like your expression “innocent voyeur”!

Hi Parmanu,

thanks for this – very pleased you liked the book!

Jai

Very pleased you wrote the book, Jai!