1. The foreigner

My visit to Bangalore is part business-trip part vacation. Traveling with me on business is a German colleague whose eyes reveal a side of the city I usually gloss over. On the first day, he is puzzled by the security measures at the hotel entrance. Our bags are scanned, the contents of our pockets verified, and we pass through a metal detector. The shopping mall attached to the Marriott has another checkpoint. Why so many security checks here, he asks, when everything seems normal outside?

It is his first visit to the country. On the afternoon he arrives, he takes an auto-rickshaw to Bangalore Palace, and later sends me a picture of the rickshaw on WhatsApp. He is curious about Indian food, but soon runs into “stomach issues due to the spice.” At the restaurant, he tries to make sense of the waiters in the scene, some flitting from table to table, others hanging around doing nothing, and a few just giving orders to others. In the evening he goes looking for mineral water — the bottles in his room are exorbitantly priced — but the nearby BigBasket outlet has no stock. In another supermarket at another mall he picks up four water bottles — it is all they have. Why do supermarkets here not stock water? he asks. I am equally puzzled.

But I am not puzzled when the security guards ignore me and wish him Good Morning. And it is no surprise to see the Crossword bookstore attendant approach him with a greeting and ask if he needs help. Why didn’t he ask you, my colleague wants to know. Because I’m not white, I tell him.

2. The dog walker

The streets I see through car windows are mostly dug up for construction, either for the metro or a flyover. Driving through this traffic is arduous, to put it mildly, but the locals somehow manage. When the metro construction began outside our office building a year ago, my colleagues here talked about it in every other conference call; these days I rarely hear a murmur. What begins as an inconvenience turns into a routine. The hedonic treadmill: even visitors like me are not immune to it. After half a dozen Uber rides, I find myself getting used to the congestion. One reason is the fascinating display of street-side life that appears as we crawl past. It’s like a living museum: beautiful and grotesque, calm and frenetic, joyous and gloomy, unending.

Street-side garbage is a permanent exhibit in this museum. But on this matter locals seem to be taking action. At the Independence Day celebrations in our apartment complex, a young man in a kurta speaks about his solo efforts — on morning walks with his dog — to remove notices and signboards stuck on trees. These improvised signs are illegal and ugly, he says. His insight, after months of this practice, is that there is no conclusion to such attempts — it’s an ongoing process, a steady and constant push to keep our neighborhoods clean. This speech is followed by a short musical staged by five to eight-year-olds on the theme of Swachh Bharath (Clean India). It begins with Gandhi’s efforts to help Bharath Maa free herself from British hands and ends with a movement to rid the country of its filth.

On a walk through the neighborhood later that day, I find encouraging results of a local drive to clean up a playground corner. Previously used as a litter dump, this corner now looks almost elegant. The earth has been recently dug-up and the tree bases cleaned and whitewashed. Old car tyres painted red, yellow, and blue stand like makeshift seats for children. This could be a private backyard of someone’s house.

But only a few feet away, on the footpath running in front of a brand new “e-toilet”, there is evidence of shit. Dog shit. The mounds are round and shiny, probably the produce of a well-bred animal belonging to one of the upper-middle-class folks who walk their dogs here each morning. An image springs to mind. The dog walker who gave the speech that morning is ripping out notices from a tree, while his stylishly-collared German Shepherd poops on the footpath behind him.

3. The e-Doctor

The ads on TV reveal a shift towards online products — Swiggy, Flipkart, Idea 4G, BigBasket— which mirrors the rise in e-commerce here. On every visit to this city I find myself acquiring the local online habits. I cannot imagine myself doing all this in Germany, but here in Bangalore I order food home via Swiggy, buy clothes on Myntra, use Uber to get around, and sign-in apartment visitors using myGate.

But this time I go further. I place my health at the mercy of an app.

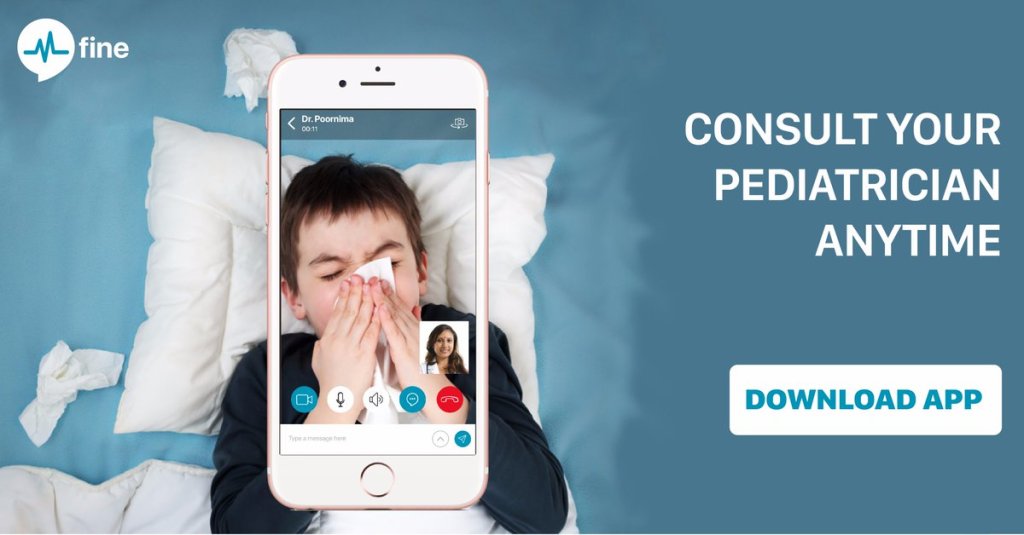

mFine is a new healthcare startup that promises to connect you to a doctor in sixty seconds. It really does. Someone appears on a chat inside the mFine iPhone app, introduces himself as an assistant doctor, and asks me questions about my health issue (throat and ear ache), my medical history, and the medicines I’ve recently used to treat myself. He then schedules an appointment with the doctor I’ve already chosen at the beginning, from a list of doctor profiles. Thirty minutes later I receive a call from a customer service rep, with a hint that my chat with the doctor will begin shortly. I open the app again, and there she is, Dr. M, introducing herself. I’ve looked at your case, she says, and here is your prescription. A PDF document appears. Opening it, I find a prescription for an antibiotic, a paracetamol, and a solution for gargling. The ear ache is due to a throat infection, she clarifies, before advising me to inhale steam and gargle regularly. I thank her and log off. The consultation with both doctor and assistant lasts twenty minutes and costs me five hundred rupees. I stay in bed through it all.

My case — as a visitor in this city — is a perhaps a one-off, but for people living here I can see how this app can be handy in simple consultations like these. Visiting a doctor can be put off until it is imperative; in Bangalore, with its inertia-inducing traffic, this can be a blessing. It can also be a blessing when you are traveling: a first opinion from a familiar doctor can be soothing in an unfamiliar land. And if you have a recurring condition like high blood pressure or diabetes, the online channel can speed up consultation with your regular physician.

The benefits of online consultation do not end here. Over time the app will gather the history of your ailments and treatments — what was with a doctor before is now on your phone. If the data privacy and security bits are handled well, all this digital information in one place can eliminate unnecessary procedures (like filling medical-history forms and repeating tests) when you switch doctors or consult another expert. It can also be the ideal source for keeping track of and improving your health. Further on, increasing sophistication of personal medical devices will allow the app to handle more complex cases. (The Apple Watch that can generate your ECG at the touch of a button is one recent example of the potential here.) Visiting a doctor for a consultation could become an exception, not the norm. At least this is what mFine envisions.

For a generation that has grown up with doctor visits, it is an unsettling vision. What about the doctor’s touch? Can the impersonal chat (or a video call) substitute the comfort a doctor offers in person? What about the value of a physical examination?

I suspect these concerns are more relevant for serious or complex cases, situations where we feel a strong need to be examined by a doctor in person. But even here the app — and associated personal medical devices — can reduce the time we spend in clinics shuttling from one test to another. The time at a doctor’s clinic will then be used for what’s most important: the interaction with your doctor.

Such cases will be the litmus test for the market potential of these apps. There’s a leap of faith needed to skip visiting the clinic for non-trivial ailments, and as long as consumers avoid taking that leap, the reach of such apps will be limited to simple conditions. These simple cases will not generate the volume of business we’ve been seeing with e-Commerce. On Myntra, I shopped for clothes and shoes worth over ten thousand rupees last year; this time on mFine the bill stays, thankfully, at five hundred.

Ten years ago I’d have laughed at anyone telling me I’d spend all that money shopping for clothes online. But Myntra, and the community using such online services, nudged me forward. Today it may be hard to imagine ceding control of your health to an app, and this switch, if it happens, will not come soon. But the confidence we gain from simple cases will encourage some of us to trust this channel more. As this community of early adopters grows, and as personal medical devices become accessible and common, services like mFine will appear less unconventional and more essential.

Five years on I won’t be the outlier I feel like today.

4. The scientist

A play at Ranga Shankara is a regular feature of my Bangalore visits, and this time I watch Photograph 51, a play by Anna Ziegler:

The play is about the race to solve the structure of the DNA and the role of Rosalind Franklin who provided the critical evidence for this. For a long time, she never got the credit and this play highlights her efforts in science at a time when the doors of science were not open for women.

It’s a brilliant play, and the performance is superb. What strikes me is the structure. The play begins with all characters on stage, some at the center and others on the periphery, and as in life the marginal characters occasionally take the spot lit center stage. Watson and Crick, whom we associate with the DNA double helical structure, are at the margins here. This is not their story; it is Rosalind Franklin’s story. She’s at the center for most of the play and deserves every moment of it.

Photograph 51 works for me because there’s an ambiguity about the cause of Franklin’s fate. Why do we not remember her for revealing the structure of the DNA? Was it because Watson and Crick used Franklin’s results without giving her the credit she deserved? Could she have independently followed the direction they did, creating a DNA model and working on a theory, instead — as she chose — of relying only on experimental results to provide answers? Or could she have been more open to collaborating with her colleague, Dr.Wilkins? Things could have gone differently, the play suggests, and we will never know. But Franklin was up against a scientific establishment with little regard for women scientists, and this comes through strongly in the play.

Among the theater audience on this day are Narayana Murthy, the co-founder of Infosys, and his wife Sudha Murthy, a writer whose books in Kannada and English are prominently displayed in local bookstores. But the buzz in the theater is really about the man. I wonder if anyone catches the irony behind this, on an occasion that brings into focus a woman’s role in a sphere dominated by men.

5. The wedding

I’ve extended my stay in the city to attend my cousin’s wedding. The daughter of my mother’s brother, she lives in Seattle and works for Microsoft. Her fiancé, soon to be husband, works for Intel.

My mother is one among nine siblings. Cousins on this side of the family who now live in distant countries are gathered here for the event. It’s a three-day affair, marked by rituals that typify South Indian brahmin weddings. And accompanying the rituals is a cornucopia of sights common to these occasions: the glitter of gold and diamonds, the radiant palette of silk sarees, the sanctioned gluttony of plantain-leaf meals, and the miasma of complaining relatives — all of which I can recall from my wedding almost twenty years ago. Twenty years is a long time. What has changed?

Social constructs remain rigid and unchanged. The wedding rituals, the practice of giving and receiving lavish gifts, the generosity expected from the hosts, the extravagance of the event itself – there’s all of this, and against this backdrop, watching my uncles and aunts now and recalling how they looked at my wedding, I suddenly notice that they seem old and shrunken. My cousins too have grown older, and some now appear, in my imagination, to take their parent’s places. The circle of life goes on.

Technology is another matter, and the difference here is self-evident. Smart phones, selfies, instant sharing on social media, video chats with friends abroad, digital coupons as wedding gifts, Fitbits and smart watches — things we take for granted today are on display. There’s even a drone flying around the wedding hall, capturing aerial photos and video.

Then there is material wealth. The upper middle-class people attending these weddings are vastly richer now, a fact visible, for instance, in the cars they drive, the jewelry they wear, and the higher percentage of relatives and friends visiting from abroad. Looking at my relatives it seems that (keeping aside inflation) their wealth has gone up tenfold or more in these twenty years.

But turning towards the cleaners at the wedding hall, you see a darker side. They all wear the same cloak of poverty. The look of tiredness they carry is disturbingly familiar. And the indifference of the guests to these cleaners, who squat in a corner as the guests eat and laugh, has also not changed. (I am indifferent too; spotting them I feel a sting of emotion I cannot place, but a few moments later they are out of my mind.)

I have no answers here, and even questions seem pointless. After all these visits to the country, after the unchanging pattern of being disturbed (by the shocking inequality that hits you here) followed by being indifferent, I wonder if this is even worth noting if one cannot act on it. Here’s Naipaul, at the beginning of his 1962 book An Area of Darkness:

They tell the story of the Sikh who, returning to India after many years, sat down among his suitcases on the Bombay docks and wept. He had forgotten what Indian poverty was like. It is an Indian story, in its arrangement of figure and properties, its melodrama, its pathos. It is Indian above all in its attitude to poverty as something which, thought about from time to time in the midst of other preoccupations, releases the sweetest of emotions. This is poverty, our especial poverty, and how sad it is!

… India is the poorest country in the world. Therefore, to see its poverty is to make an observation of no value; a thousand newcomers to the country before you have seen and said as you. And not only newcomers. Our own sons and daughters, when they return from Europe and America, have spoken in your very words. Do not think your anger and contempt are marks of your sensitivity.

What is remarkable about these lines is that they were written after Naipaul’s first visit to India, when he was barely thirty. What’s also striking is that five and half decades hence so little has changed.

So was the MFine diagnosis and medicines good for you? and yes, the inequality is huge but what I get bothered about is the attitude of the haves towards the have-nots. Something has gone terribly wrong with our society

Have south Indian Brahmin weddings adopted the mehndi ceremony? We Malloos never used to have all this (our weddings were blink-and-you-missed-it fast) but now nobody is satisfied with such a short affair.

I went to see Photograph 51 a few years ago (Nicole Kidman in the Franklin role) – it was a very good production. Who did the role in Bangalore?

A pleasure as ever to read your posts.

Oh yes, mehndi is pretty common these days. Folks have it even before thread ceremonies (upanayanams)!

About who did the role … I seem to have no recollection of the name.